By Richard Clements

Following on from my recent piece about liminal spaces, I kept thinking back to a story that does not come from folklore or archaeology but from one of the most dramatic survival accounts ever written. Shackleton has appeared on the outskirts of a few bits of LifesQuest research, never tied directly to anything we were exploring, yet somehow always close by. While writing about places where the world feels thinner, his name kept returning to mind.

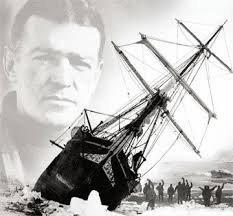

I have always been drawn to the early polar expeditions. The silence, the scale of the landscape, and the way hardship strips a person down to their foundations have fascinated me for years. Shackleton’s voyage with the Endurance stands out in a way few stories do. The deeper you look, the more it seems to sit partly in fact and partly in a space that is harder to pin down.

And at the heart of it is the moment when three exhausted men believed they were not alone.

Before the Crossing

The Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition began in 1914 with the aim of crossing Antarctica. The plan unravelled early. The Endurance became trapped in the pack ice in 1915 and drifted helplessly for months until the pressure finally crushed her. When the ship slipped beneath the ice, the crew were left camped on drifting floes with only their tents, limited supplies and three open boats.

They stayed on the ice for as long as they dared. When the floe began to crack under them, they launched the boats and rowed through freezing waters towards the nearest hope of land. After days of hardship, they reached Elephant Island, a barren refuge far from any shipping routes.

Knowing they would not survive if they remained there, Shackleton chose five men to attempt the 800-mile journey to South Georgia in the small lifeboat James Caird. Battling storms and freezing spray, and guided by the briefest glimpses of sun for navigation, they somehow reached their destination.

But the whaling stations lay on the far side of the island. To reach help, Shackleton, Frank Worsley and Tom Crean had to cross the uncharted mountains with barely any food and almost no strength left.

The Presence on the Ice

The three men walked for roughly thirty-six hours without stopping. They climbed ridges, crossed glaciers and forced themselves onwards through exhaustion. Somewhere in that strange, dream-like march, a deeper oddity crept in.

Shackleton later wrote that it often felt as though a fourth figure was walking with them. He kept this to himself at the time, not wanting to unsettle the others. Only much later did he discover that Worsley and Crean had held the same thought, each believing that an unseen companion was beside them.

There was no voice and no clear shape. Only the steady sense that someone else shared their path.

Others Who Felt the Same

This kind of experience is not unique. People pushed far beyond their limits have described the same thing. Climbers lost in storms. Sailors drifting alone at sea. Miners trapped deep underground. Reinhold Messner felt it on Nanga Parbat. Charles Lindbergh wrote about a similar presence during his long flight. Teams of explorers in both polar regions have mentioned the same quiet feeling.

The details vary, but the theme is constant. When life hangs in the balance, the sense of a companion sometimes appears.

Antarctica as a Liminal World

If liminality describes the space between one state and another, then Antarctica during Shackleton’s time was the most dramatic version imaginable. The continent sits on the edge of the known world. Sea becomes ice. Light becomes darkness for months at a time. Boundaries shift constantly, blurring the usual markers that give people a sense of place.

The Endurance ordeal pushed the crew into a kind of suspended existence. They were neither secure nor entirely defeated. They lived day by day on moving ice, trapped between worlds. Everything familiar fell away.

Crossing South Georgia was the final threshold. It lay between survival and disaster, between despair and the faint hope that help might still be found. Exhaustion stripped the men to their core. Only their intention kept them walking.

In that strange, fragile state, the presence makes its own kind of sense.

A Threshold of Mind and Landscape

Some psychologists see the Third Man experience as a coping mechanism, the mind creating a guide or companion to hold a person steady. It is a reasonable idea. Extreme conditions can produce remarkable clarity or unusual impressions.

Yet Shackleton’s account holds an atmosphere that feels different. All three men sensed the same thing, without sharing their thoughts. Even T. S. Eliot was drawn to the story, weaving it into The Waste Land with the lines about the mysterious “third who walks always beside you.”

The landscape itself plays a part. A person suspended between exhaustion and purpose, surrounded by a world that is already a threshold, may be far more open to impressions that normally sit just out of reach.

Whether the presence came from the mind or from somewhere beyond it, it arrived when they were walking the thinnest line imaginable.

A Parallel with Psychic Questing

Shackleton’s experience was born of desperation, yet I often think of it when considering something much gentler: psychic questing. At its best, questing is simply a way of entering a place with full attention. Historical research provides one guide. Intuition provides another. You listen to the land, the ruins, the quiet boundaries, and allow the place to speak in its own way.

It is not about forcing anything. It is about awareness. And in that sense, it shares a distant echo of what Shackleton’s group felt. They were stripped bare by hardship; the quester strips things back by intention. Both situations soften the usual boundaries of perception.

The Return and Rescue

Once Shackleton, Worsley and Crean reached Stromness, they raised the alarm immediately. Shackleton tried again and again to reach Elephant Island, turning back only when the ice forced him to retreat. On the fourth attempt he broke through. Every man from the original crew was still alive. Not one had been lost.

The rescue remains one of the most remarkable in exploration history.

Closing Thoughts

Shackleton’s story sits somewhere on the edge between the clear and the mysterious. Some of it fits comfortably within psychology. Some of it points towards experiences we barely have the language to explain. Often it is a mixture of the two.

Liminal places are not always found in the landscape. Sometimes they appear in moments of exhaustion, fear or determination. Sometimes they form around a person rather than a doorway or a shoreline.

Whether the fourth presence was imagined or real, it walked with them long enough to be remembered. And stories like this remind us that there are edges in human experience that we rarely examine closely. Perhaps they are worth paying attention to.

References

- Ernest Shackleton, South: The Story of Shackleton’s Last Expedition 1914–1917, Macmillan, 1919.

- John Geiger, The Third Man Factor: Surviving the Impossible, Weinstein Books, 2009.

- Reinhold Messner, The Crystal Horizon, Mountaineers Books, 1991.

- Arnold van Gennep, The Rites of Passage, University of Chicago Press, 1960.

- T. S. Eliot, The Waste Land, Boni & Liveright, 1922.

- Caroline Alexander, The Endurance, Bloomsbury, 1998.

- Roland Huntford, Shackleton, Hodder & Stoughton, 1985.